Week Twenty-Eight: Double Indemnity (1944)

Director: Billy Wilder

Producer: Joseph Sistrom

Writers: Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler

Cinematography: John Seitz

Music: Miklós Rózsa

Studio: Paramount

Studio: Paramount

Starring: Fred MacMurray (Walter Neff), Barbara Stanwyck (Phyllis Dietrichson), Edward G. Robinson (Barton Keyes), Porter Hall (Mr. Jackson), Jean Heather (Lola Dietrichson), Tom Powers (Mr. Dietrichson), Byron Barr (Nino Zachetti), Richard Gaines (Mr. Norton)

Despite all the great musicals and war films released in the

forties (including everyone’s favorite, Casablanca)

the decade belong to film noir without a doubt. Not only did noir become a

major genre throughout the middle and end of the decade, noirish characteristics and visual style infiltrated numerous other genres.

The look of noir, which we’ve touched on slightly in previous

weeks, is the most obvious characteristic of the genre. Noir visuals have a

strong base in German Expressionism, particularly the high contrast, low-key

photography utilized by the likes of F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, and Josef von

Sternberg during the twenties and thirties.

|

| High-contrast or "chiaroscuro" photography: the level of difference between the dark and light aspects of the composition. |

|

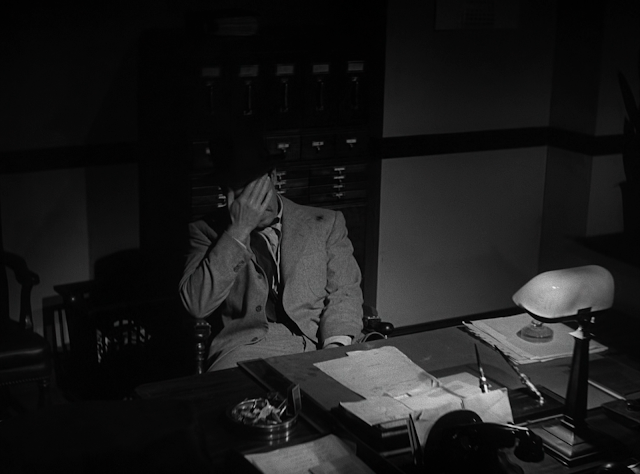

| Low-key photography: a low level of overall brightness in the composition, in film noir the "key" lights often come sources within the scene, such as Walter's lamp. |

In Double Indemnity, the most common use of high contrast photography comes from the so-called "Venetian Blind effect" in which the frame is slashed by the shadows created from light coming through blinds. Not only does this give the film a dynamic look, but it doubles as a visual representation of prison bars.

|

| The soon to be ubiquitous Venetian blind effect, thanks to John Seitz work on Double Indemnity. The film didn't invent the effect, but its success popularized it. |

Like the twenties Expressionists, noir

visuals often incorporated heavy use of shadows and more unorthodox camera

angles, including from low angles so that ceiling was visible. This was not a

normal practice, as most sets were built without a ceiling and a low angle shot

would just show the top of the soundstage. The more that noir took hold, the

greater the expressionist influence became, particularly under directors like

Robert Siodmak, who put shadows, silhouettes and unusual camera angles front

and center in their films.

However, the visual style of noir has often led to confusion

on what should be considered part of the genre, as by the end of the forties

pretty much every film looked like a noir. The “noir style” of visuals became

the look of the decade itself. Noir can be confirmed by its look but not

identified. For example, Leave Her to

Heaven (1945) is undoubtedly a noir but also happens to be filmed in

beautiful, bright Technicolor. On the other hand, Casablanca looks like a noir but isn’t one.

We can identify noir first and foremost not by its visual

style but by it’s characters, themes, and plot. Noir comprised of a

contradictory combination of elements, beginning with the highly realistic

setting. Noir is set in real places without any addition of fantastical

elements; it almost always focuses on common events and stories, though often

stocked with unusual characters. Double

Indemnity is set in and around Los Angeles and film in multiple real,

middle-class locations that suited the middle-class characters in the film: an insurance salesman and a housewife. Married to that narrative realism is the

strong element of visual expressionism, of non-traditional visual compositions

that reflect the story that is unfolding. Even more contradictory to the

realistic setting and stories is the simple fact that noir is above all else

quite weird and in many cases aspects of the films take on a dreamlike quality,

despite their nominally normal setting.

|

| Realistic, un-glamorous settings are characteristic of noir. |

|

| Wilder and Seitz spilled cigarette ashes and threw alluminum particles in the air to create a lived-in, dirty enviroment, representative of Phyllis' disinterest in domestic duties... |

|

| ...and Walter's bachelor lifestyle. |

Another aspect of noir that pushes against the realistic

setting is the frequent presence of some sort of fate, of characters that are doomed no

matter what actions they take. They are rarely in control of their own destiny,

subject to the heartlessly balancing scales of justice. Noir is almost always

built around the committing of some type of crime, whether it be the robbery of

a jewelry store or the murder of a spouse. Before noir, Hollywood films almost

always had the criminals as the bad guys, however in noir the “protagonist” has

usually committed some sort of a crime or operates in a moral grey area. Here

was see the influence of films like M or

Scarface that tell the story from the

criminals point of view. This abundance of crime leads to another key part of the

noir formula: violence. People die in all types of movies, even comedies and

musicals, but noir is different. Not only is the violence pervasive and central

to the story, it is often extreme, with body counts piling up and torture a

frequent tool of characters on both sides of the law. Early gangster pictures,

with criminal protagonists and violence galore, shared some of these elements

but noir is different, often focusing in on regular people not hardened

criminals and with more personal violence. Killing people is Tony Camonte’s

line, it is just business, but when the average next door neighbor kills their

spouse in a fit of passion, it is a very different thing altogether.

A common theme in noir is the examination of the dark underbelly of otherwise a gleaming society. In Double Indemnity, the killers are normal people living normal lives who are driven by greed and lust (two common desires any average person can experience) and they meet in public, innocuous places. The implication isn’t just that the man in front of you in line may be a murderer, but that criminals can hide in plain sight and even the most respectable person can turn to crime at a moments notice because what society views as respectable is just a veneer, no one knows the darkness and passions that lurk within.

A common theme in noir is the examination of the dark underbelly of otherwise a gleaming society. In Double Indemnity, the killers are normal people living normal lives who are driven by greed and lust (two common desires any average person can experience) and they meet in public, innocuous places. The implication isn’t just that the man in front of you in line may be a murderer, but that criminals can hide in plain sight and even the most respectable person can turn to crime at a moments notice because what society views as respectable is just a veneer, no one knows the darkness and passions that lurk within.

|

| Walter and Phyllis have clandestine meetings at mundane, everyday places like the supermarket. |

This focus on the average person becoming a criminal leads to

another aspect of noir: never before has the dark psychology of killers and

madmen been so prevalent on the screen. Some noir killers aren’t only murders,

they are sadists who gain pleasure from the pain they inflict. There is an almost romantic relationship between William Bendix and Alan Ladd's characters in The Glass Key (1942) with the former taking sadistic pleasure in beating latter and playfully calling him by the pet name "Baby." Elsewhere, Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea's characters in Scarlet Street (1945) have a passionate romantic relationship that just happens to include him beating her on occasion with the film strongly hinting that she likes it. Even those that

don’t enjoy violence and suffering have their motivations and desires unraveled

by the end of the film. This goes hand in hand with the

development of the noir anti-hero, as audiences need to still be able to root

for characters even if they did bad things. If the hypothetical normal next

door neighbor kills their spouse because he is unfaithful and abusive, then it

is much easier to be on their side, even if we know they must pay for their

crime. Walter Neff in Double Indemnity is

a prime example of this, he is charming and relatable, no matter what he does.

Part of this is due to Fred MacMurray, who had previously been the hero of

romantic comedies, training that allowed him to win over the audience while

also unlocking a previously unknown harder edge. Not only are the lines between criminal and good guy blurred in

noir, but frequently there is little distinction between law and crime, with

many of the police and city officials just as bad as the criminals, corrupt or

straight up villainous.

Additionally, noir often has an erotic element. Adultery is

almost as prevalent as murder in these movies. Love and sex often serves as a

motivator towards the committing of crimes, with a femme fatale often the instigator, using her sensuality as a motivating

factor to control weaker will men. Some variation of “kill my husband so we can

be together,” or “embezzle from your company so you can keep me in mink,” are

both common noir plot lines.

|

| Barbara Stanwyck's Phyllis Dietrichson is one of the first forties noir femme fatales. |

The films of Fritz Lang as well as the gangster movie genre

were definitely influential on the genre, but not as much as the crime stories

written in the twenties and thirties by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and

James M. Cain. In these books we find not only the distinctive themes, plots,

and formulas of noir but also the language of the genre, the hardboiled way of

speaking, and frequent first person narration. Not surprisingly, Double Indemnity – one of the most

characteristic films of the noir genre – was co-written by Chandler and based

on a novel by Cain.

|

| Crime author Raymond Chandler's cameo in the film. |

Joining Chandler on the screenplay was director Billy Wilder, who

shared he co-writers ability to turn an clever or acidic line of dialogue,

something that is abundant in Double

Indemnity. Chandler only had the opportunity to work with Wilder because

the director’s usually collaborator, Charles Brackett, didn’t want to be

involved in the writing of a such a lurid and tasteless movie. Such was the

standing of noir type films when Double

Indemnity was made, though many of those thoughts would change after the

film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, though it shamefully didn’t win any.

Perhaps the most egregious snubbing was composer Miklós Rózsa not winning for Best Musical Score.

Rózsa was one of the most creative and talented composers working Hollywood at

this time and his work on Double Indemnity

might be the best of his career. Complex and resonant, Rózsa’s score serves to

add both tension and an deep sense of foreboding to a film filled with both.

After You Watch the Movie (Spoilers Below)

Though the cleverness of his dialogue often gains Wilder the

most acclaim, it is the way he and his collaborators structure their stories

that makes them standout. Double Indemnity

begins at the end, with a bleeding Walter relating the film into his

Dictaphone. This is key to the film because it lets Walter narrate the whole

story, which allows for the classic first-person narration of Hammett,

Chandler, and Cain’s novels to be easily translated to the screen. It also

clearly lays out Walter’s motivations (“I killed him for money and a woman –

and I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman.”) and gives us an

intimate look at the thought process and feelings of a murderer.

|

| Double Indemnity's flashback structure opened up a number of storytelling opportunities. |

By laying out

the film in flashback, it makes it clear that this is not a mystery film, since

we know right off the bat that Walter is a murderer but doesn’t get the money

or the girl. In fact, Double Indemnity

is the opposite of a mystery, it is everything that leads up the crime, the

crime itself, and the falling out of the killers. Many noir, including Double Indemnity, is told from the point of view of the criminal that commits the

crime. Keyes’ investigation is nothing like a detective tale, instead it is a

suspense story in which we watch with bated breath wondering when it will all

unravel.

|

| Never mind the door opening out, it's a movie! |

|

| Phyllis' and Walter are always just on the precipice of being found out. |

|

| The collapse of the killers relationship: in the first supermarket scene, Walter and Phyllis are united and stay side-by-side... |

|

| ...in the second, after they fight they are shown separated both emotionally and physically. |

Noir is rarely interested in mysteries, clues, or investigations, it’s

focus is on the criminals motivations and feelings before, during, and after a

crime. The fact that the film begins at the end also gives the overall story a

noirish sense of fate and inevitability. We know Walter is doomed and, even

when he turns Phyllis down the first time we know he won’t be able to resist

forever.

A final, quite important aspect of the flashback is the principle of

hindsight bias. Essentially, if they audience knows something happens (in this

case, Walter and Phyllis kill her husband and then things fall apart and Walter

is shot) then they are inherently much more accepting of whatever steps lead to

that outcome. For example, if we know that a man and a woman end up married,

then during the flashbacks to when they first meet, audiences will be much less

likely to question the improbability of their meeting. This principle is used

all the time by screenwriters because it is so effective.

The voiceover would soon become a noir staple and one of the

most parodies elements of the genre, along with the dialogue. Again, Double Indemnity is an archetypal film

in this regard. Walter’s idiosyncratic voiceover (“How could I have known that

murder could sometimes smell like honeysuckle?”) and the back-and-forth,

innuendo laden dialogue between Walter and Phyllis (“I wonder if I know what

you mean.” “I wonder if you wonder.”) is characteristic of the stylized nature

of the genre’s characters. Despite noir’s grounded settings, people don’t talk

like this in real life but who wants to watch a movie about people in real

life?

In addition to it’s visuals, story, and dialogue, Double Indemnity was also

ground-breaking in it’s stark and open depiction of sensuality and sex. Not

only do the innuendos fly fast and furious, but the subtext is quite apparent

as both Walter and Phyllis’ faces and bodies leave no doubt about what they

want and eventually do.

|

| The lust apparent in Walter and Phyllis' first meeting is barely disguised. |

|

| Early in the film, a low angle shot of Phyllis shows the power her sensuality gives her... |

|

| ...over a low angle, lustful Walter. |

|

| At the end of the film this dynamic is reversed, with Walter now in control of the situation. |

This intermingling of sex and violence (“It's just like

the first time I came here, isn't it? We were talking about automobile

insurance, only you were thinking about murder. And I was thinking about that

anklet”) is a key aspect of noir that would only be expanded upon in further

films.

|

| Before and after: Hollywood shorthand for sex. |

A key factor in this is Phyllis, as embodied by the brilliant

Barbara Stanwyck, one of the templates for the noir femme fatale. As is typical of the archetype, Phyllis uses Walter’s

lust to her own ends and almost manipulates Nino into getting Walter out of the

way too. Walter eventually out-foxes her, but it is still her bullet that

brings his life to an end. Phyllis also derives pleasure from a mix of

violence, lust, and murder, matching Walter’s sadism, enjoying the anklet “cutting

into her leg."

|

| The look on restrained pleasure on Phyllis' face as Walter strangles her husband. |

|

| Walter's fetishistic fixation on Phyllis' anklet "cutting" into her leg. |

Though they are morally grey at best, the femme fatale is one of the strongest female characters type in classic Hollywood cinema. They are architects of their own destiny and are often portrayed as the stronger character in the male/female dynamic. Censors demanded that characters like Phyllis get what is coming to them, but time bears out that many of noir’s femme fatales are some of the best loved and most iconic performances of the period, far more memorable than the era’s heroic female characters. Bad girls just have more fun. The violence and finality of noir mostly exempts these women from the humiliating moral chastisement at the hands of male counterparts that women in classic movies often faced. Instead, they just get to die with their independence and dignity intact.

Double

Indemnity is far more than just a seminal noir and example of smart

story structuring, however. Most unique is the close relationship between

Walter and Keyes, friendship that Walter betrays. Though Walter and Phyllis get

the most focus of the story, Walter and Keyes’ friendship is the backbone of

the movie and what drives Walter to record his confession in the first place.

Walter isn’t remorseful about killing Phyllis’ husband, it is letting down

Keyes that he feels bad about and what justifications he gives serve more as an

explanation to his friend than anything else. This is endemic of noir, in which

criminals don’t really feel bad for what they did, they just regret hurting people

they care about.

|

| Walter didn't need to record his confession, but he felt he owed it to Keyes... |

|

| ...with whom he shared a close friendship. |

|

| " I love you too." |

Double

Indemnity was a rousing success for all involved and helped to bring

noir to the mainstream, where it would stay for the next fifteen years. Though

most of what the genre is about can be found in this film, the permutations, variations,

and exaggerations of the formula is

nearly endless, as is the pleasure that can be derived from the films

themselves.

See Also

The

Maltese Falcon (1941) dir. John Huston

If not the first film noir, then the first of the major

forties noir movement. The debut for legendary director Huston and Humphrey

Bogart’s breakout role. Mary Astor is another template for the femme fatale and M star Peter Lorre is part of an excellent supporting cast.

Laura (1944)

dir. Otto Preminger

The other great noir of 1944, Laura is an entirely different kind of film, set in the New York

upper class and revolving around the murder of a beautiful sociality.

Tremendous production values, acting, writing, directing, and music.

The Big

Sleep (1946) dir. Howard Hawks

Based on a novel by Raymond Chandler, Bogart gives another

stellar performance on his way to being kind of the noir. A twisting turning

plot stuffed with killings and hardboiled talk. One of the best of the genre.

Out of

the Past (1947) dir. Jacques Tourneur

The quintessential film noir about a doomed man and the femme fatale he just couldn’t quit. Star

Robert Mitchum was made for the genre and his pairing with Jane Greer is

dynamite. No film embodies the look and feel of the genre more so than this.

Let me know what you think either here or on Twitter @bottlesofsmoke

Comments

Post a Comment